How, though, was I going to do that? When test day rolled around, should I just sit down in my school’s cafeteria with my soft # 2 pencil – along with hundreds of others lined up at tables – and start frantically filling in the little bubbles on the score sheet? Or should I actually study for a test that caused many students nightmares and sweats? Back then, conventional wisdom had it that studying for the SAT was a big waste of time: the “A” in SAT stood for aptitude, and you supposedly either had the juice or not. The Federal Trade Commission would soon go on to investigate Stanley H. Kaplan’s claim that a student taking his one of his SAT test prep classes could expect a score increase of a hundred points or more. They found that the average person could hope to gain only a measly 25 points!

That kind of pessimism and smug conviction – that intelligence is fixed – seemed wrong to me. I never wanted to believe in conventional wisdom. I thought that a highly motivated person, using the right means, could achieve almost anything.

A Perfect 800 SAT Score

And so I went out and bought a book of practice SAT questions and began working through it. I had no choice, as no one offered an SAT prep course in my small town.

I took my first SAT and scored in the low 700’s on the math section and the low low 600’s on the verbal. That wasn’t good enough. (Though at the time, before the test was recentered in 1994, a score in the low 700s was like a score in the upper 700s today, and perfect 800 scores were extremely rare). I studied some more, and I started becoming familiar with the types of test questions and the pace of the test. I took the SAT again, and I raised my combined score by a total of about 100 points. That, however, still wasn’t good enough.

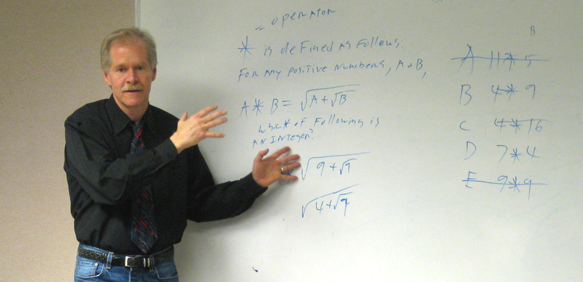

And so I studied still more, even harder. I did as much SAT prep as I could. I cut school to pour through sample reading comprehension passages and to do math problems by the hundred. I began noticing patterns: in almost every set of reading comprehension questions, one question would ask me to identify the main idea of the passage. On the math section, if I saw a circle with a shaded region, it was a pretty good bet that I would need to calculate its area by subtracting the area of the unshaded region from that of the whole circle – or vice versa. I learned which kinds of problems I could do in a breeze and which caused me to struggle. In this way, I began developing some of the skills and techniques that would later become part of my coaching courses. Although I wouldn’t have put it like this when I was sixteen, I began coaching myself.

The third time I took the SAT, I surprised all my friends by gaining even more points on the verbal section, for I had always done poorly in English and I didn’t know how to write. On the math section, I scored a perfect 800: the only one in my high school of 3,000 students to do so. I felt pretty sure that I had gotten every problem right. After that, good universities actually offered me scholarships. This whole experience did two things: it confirmed the importance of admissions tests and convinced me that we all have much greater “aptitudes” than we dream.

My First Two Students

Fast forward a few more than a few years. In much the same way that I had coached myself to take the SAT, I taught myself how to write. I wrote… a lot: big novels that were nominated for awards. About my work, the London Times Literary Supplement said, “Zindell has placed himself at the forefront of literary SF.” I found a deeper creativity in having children of my own. In considering how our educational system often fails so many bright young beings – and that people usually learn best with personal attention – it seemed the best course to school my daughters at home.

They both thrived. My oldest daughter, Justine, published her first poem when she was only six years old. When she was sixteen, I took a few weeks out from my novel writing to work on a series of essays that would accompany some brilliant photographs of rocks in a book called Within The Stone. I paid Justine $100 out of my advance to write one of my ten essays. She took to the project with joy. When her brilliant essay was published along with mine – and side by side with the work of fine writers such as John Horgan and the poet Diane Ackerman – she became a professional author. My youngest daughter, Jillian, very early began elaborating her own unique art form: her swirling, geometric compositions, done in pen and ink, called to mind archetypes out of nature and the human soul, and astonished many with their beauty. Justine began writing screenplays and directing films staring Jillian. Both my daughters attained second degree black belts in Soo Bahk Do, and while still teenagers they ran their own karate school. Both of them wanted to go to the same university from which their parents had graduated. As they would need good SAT scores to support the grades they received for their home study, I coached them in individually designed SAT prep classes. They did well enough to receive early acceptances. And Justine accomplished what I never quite managed myself, blowing through the verbal section with her own perfect 800.

The Real Reason I Love Coaching

That was the real beginning of my coaching career. Over the years I like to think I’ve grown not only older but a little wiser. These days, even though many students don’t do very well in traditional, over-crowded classrooms, I wouldn’t advise anyone to cut school to study for the SAT or other admissions tests. I would, and do, urge students to seek the best possible coaching in order to overcome any gaps in their learning and to awaken their true talent. I have taken great satisfaction in seeing those I’ve coached really “get it.” My foreign students, after taking one of my GRE prep courses, have increased their scores by hundreds of points. They’ve gone on to gain admission to Ph.D. programs at prestigious universities across America. I have worked with Denver’s top investment bankers on the writing skills necessary to come out on top of their very competitive industry and to succeed on the very difficult GMAT.

As I’ve watched more and more students get into good colleges and graduate schools, I’ve come to see that my deeper reason for wanting to coach people and to write books is really one and the same. I believe in our power to learn without bound and to make ourselves into better, brighter beings. All of my novels concern evolution and the infinite possibilities of the human race. The word I chose to exemplify our true potential – and the title of my most recent book – is Splendor. Although acing admission tests such as the SAT and GRE makes up only a small part of our collective splendor, I see it as a vital part. Maybe someday we’ll evolve a whole new system for deciding who gets to attend our great universities; or better, maybe we’ll make a great education accessible to everyone. Until we do, however, those wishing to develop themselves to the highest level are going to have to take an admission test. Only then will they get the chance to learn as they should, to touch brilliant minds, and to really shine.

Learn More About David